Indigenous Learning Series Engagement Process Report: July 2018

Engagement Process Report – July 2018

[ Click on the images to see the text version ]

A circle with images forming another circle within it, surrounding the words Recognition, Respect, Relationships and Reconciliation. The images in the circle are a large feather, a smaller feather, a turtle, a large feather, a smaller feather, an infinity symbol, a smaller feather, a large feather and an inuksuk.

The Canada School of Public Service wishes to acknowledge and thank its key partners in the engagement process:

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs CanadaNote1

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation

- Provincial Health Services Authority in British Columbia

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

The success of the engagement sessions is due in no small part to the dedicated individuals from these organizations who collaborated with the School throughout this process. These ongoing partnerships will continue to be vital to success as the Indigenous Learning Series moves forward.

Table of contents

Message from the President

Taki Sarantakis

President of the Canada School of

Public Service

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #57 asks that the government provide education to public service employees on the history of Indigenous peoples and their relationship with Canada. The Prime Minister has said that no other relationship is more important to him or to this country. Working towards reconciliation is our role as public servants; it is our duty. But more than that, it is the right thing to do. And it must be done the right way.

With this in mind, the Canada School of Public Service embarked on a journey of listening and learning through external engagement sessions in 7 Canadian cities. School officials met with Indigenous Elders, youth, communities, groups and representatives, along with educational institutions and provincial and territorial governments. At the same time, the School undertook an internal engagement effort with communities of practice and Indigenous and non-Indigenous public service employees across the country.

The goal was to collect ideas, lessons learned, existing materials and resources so that the learning series could be built from a place of knowledge and truth. This process was essential to creating a learning series that accurately reflects the experiences, perspectives and diversity of First Nations, Métis and Inuit in Canada.

My predecessor, Deputy Minister/President Wilma Vreeswijk, had the opportunity to participate in some of these sessions. She was deeply impressed by the depth of knowledge, by the experiences that were shared and especially by the passion and openness of those who were eager to bring about change in the public service.

This report summarizes these discussions and provides the School with a roadmap as it continues to build the Indigenous Learning Series. I wish to thank all the participants who took the time to inform these efforts. Together we can build a better Canada and a better federal public service, where equality and respect are at the core of everything we do.

A horizontal line of words in different fonts saying "learn about the truth," "understand why," and "head," "heart," "hands," "soul," and "spirit." The words are interspersed with images of dark trees of different sizes. There is also an outline of a head beside the word "head," a heart shape beside the word "heart," a right hand stretched out beside the word "hand," a spiral beside the word "soul" and the outline of a sun beside the word "spirit."

Executive Summary

About this report

The Canada School of Public Service (the School) is the common learning service provider for the federal public service. In response to Call to Action #57 and the Government of Canada's commitment to a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples, the School is developing an Indigenous Learning Series (ILS) intended for all public service employees. To inform the ILS, the School undertook an intensive engagement process in 2017 involving federal public service employees and Indigenous Elders, youth, communities, groups and representatives, along with educational institutions and provincial and territorial governments.

The report highlights the discussions that resulted as the School asked questions and sought input, advice and resources from more than 450 participants across the country. The engagement sessions produced great insights and authentic feedback from Indigenous peoples and public service employees alike. This report reflects the findings from the 5 key questions asked of the external groups and from the 3 key questions asked of federal public service employees. The views expressed in this report are those of the participants.

What would make the Indigenous Learning Series unsuccessful?

External participants noted the following elements that could make the ILS unsuccessful if overlooked.

- The ILS must not disregard First Nations, Métis and Inuit input and involvement.

- Similarly, the audience's input must be included; by neglecting the needs and perspectives of its audience, the ILS could disengage learners or fail to be wholly representative.

- The ILS must avoid perpetuating paternalistic views and racism by being insincere, disrespectful or dismissive towards lived realities.

- An educational approach that is dry, burdensome, procedural, not challenging enough or not focused enough on truth and empathy could fail to engage learners or teach them adequately.

- ILS learning content must not be inadequately planned or poorly resourced.

- It must not be developed without measures of accountability for the accuracy of its content or its implementation, promotion and continuity.

What do public servants need to know?

External participants and federal public service employees both explored what learners should know to develop respectful relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Knowledge

Learners should be provided with opportunities to learn about

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit histories

- contemporary realities and issues

- world views

- languages

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge

- governance

These learning opportunities should reflect the diversity and regional specificities of First Nations, Métis and Inuit across Canada. Learning material should also focus on tenets of anti-discrimination and social justice—such as addressing racism, having difficult conversations and building relationships—as well as on truth, legislation and legal rights, and the meaning and implications of reconciliation.

Skills

These should include

- personal skills (self-awareness and reflective leadership)

- interpersonal skills (cross-cultural skills, relationship building, empathy, and communication)

- skills related to social justice (anti-racism and engaging in difficult conversations)

Competencies

Similarly, targeted competencies should include

- personal competencies (compromise, awareness, and respectful behaviour)

- interpersonal competencies (intercultural abilities, engagement, consultation, and sustainable relationships)

- change-related competencies (deep change and applied learning)

What are the resources that can help inform, develop, and implement the Indigenous Learning Series?

External participants listed several resources that could help inform, develop, and implement the ILS.

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit, their networks and organizations

- experts with knowledge about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit histories, cultures, and contemporary issues

- anti-racism frameworks and diverse world views

- academia (staff, alumni, graduate students and post-secondary institutions)

- key reference material (reports, legal and legislative documentation, film, books, articles, etc.)

Finally, since a broad and diverse range of perspectives could contribute to making the learning representative and truthful, the voices of women, other visible minorities, people with disabilities and people who have undergone a change of perspective should be included.

How do we address bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism?

Both external engagement participants and federal public service employees noted several ways to address bias, stereotypes, and anti-Indigenous racism, cautioning that this is a lengthy process that requires commitment, willingness and sensitivity. Addressing discrimination includes

- understanding realities and disrupting the current ways of thinking

- involving, empowering and equipping the right people

- moving towards deeper awareness and change

- committing to undertake the full and complex journey, while acknowledging that change takes time

The ILS can contribute to these approaches if it is thoughtfully and respectfully planned, executed, supported and integrated.

How will this learning series contribute to change?

External participants were asked how the ILS would contribute to change. They noted that short-term change involves

- debunking stereotypes and reducing racism

- recognizing and leveraging the value of First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, world views and knowledge

Medium-term change involves

- developing empathy and building relationships

- introducing measurement and accountability

Finally, long-term change occurs on several levels, paving the way for sustainable and respectful relationships:

- the personal level (one-on-one dialogue, ownership of personal privilege and bias, recovering from trauma)

- the societal level (working towards equal opportunities and security and overcoming inequities)

- the systemic level (integration of cultural practices and re-evaluation of existing systems, structures and policies)

How do we continue to work with public servants to identify linkages with networks and communities and ensure Indigenous learning content is relevant and aligned?

To identify linkages, federal public servants suggested

- building a community of practice (resources, leadership and learners)

- developing key mechanisms and roles (departmental champions, WebEx or in-person awareness events)

Continuous learning, in-person discussions and follow-up surveys can also contribute to ongoing improvement of the ILS. To ensure that learning content is relevant and aligned, public servants noted that some of the courses should be applicable to all of government. Other courses, however, should be tailored to portfolios or roles. Personal resilience skills and training will also be important to equip learners for potentially uncomfortable or emotional conversations.

How do we do it?

Although this question was not specifically asked, discussions with both external participants and federal public servants raised several key considerations for ensuring the success of the ILS:

- getting the right people involved and leveraging collaboration and expertise

- carefully designing learning activities to be holistic and experiential (for example, by using cultural experiences and interactive approaches)

- making the learning approach sensitive to beliefs and psycho-social elements, focusing on

- healing and wellness

- internalized colonialism and oppression

- building cultural competence

- including measures of accountability and support

- holistically integrating the ILS within the public service and the broader conversation

Introduction

The Canada School of Public Service (the School) is the common learning service provider for the federal public service. It was created to provide a broad range of learning opportunities and to establish a culture of learning within the public service.

In response to Call to Action #57 and the Government of Canada's priority to ensure a renewed relationship with Indigenous peoples, the School is developing an Indigenous Learning Series intended for all public servants.

Call to Action #57. We call upon federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal governments to provide education to public servants on the history of Aboriginal Peoples, including the history and legacy of residential schools, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, treaties and Aboriginal rights, Indigenous law, and Aboriginal-Crown relations. This will require skills-based training in intercultural competency, conflict resolution, human rights, and anti-racism.Note2

Four images are arranged in a diagonal line. From left to right, the images are a drawing of two Canadian geese; a dream catcher with 5 feathered tassels hanging from the bottom; a dream cloud with a turtle in it coming from the dream catcher; and two people dancing.

Thousands of public service employees are responsible for meeting the Government of Canada's obligations and commitments to Indigenous peoples and for fulfilling the federal government's constitutional responsibilities. The work of these public servants directly impacts the lives of First Nations, Métis and Inuit in Canada.

In many respects, federal public service employees are the face of the Government of Canada. As such, they have an opportunity to help Canada contribute to reconciliation by gaining a deeper understanding of First Nations, Métis and Inuit culture, history and modern-day issues and by becoming increasingly competent professionally in working with and developing and delivering federal programs, policies and services that affect First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Engagement process

To ensure that the School responds to the government's priority in a respectful, inclusive, meaningful, culturally sensitive and effective manner, the School undertook an intensive engagement process in 2017. This involved internal federal public service employees and Indigenous organizations, educators and youth, as well as provincial and municipal governments and academia.

The objectives of the process were

- to obtain a clear understanding of contemporary First Nations, Métis and Inuit experiences and their history and cultures

- to build relationships and find ways to leverage existing learning products

- to ensure that First Nations, Métis and Inuit perspectives, experiences, and realities are accurately and respectfully represented in the ILS

The internal and external engagement sessions helped the School to identify key elements of the ILS and provided an opportunity to address gaps, concerns and issues through open and respectful dialogue and facilitated discussion. The sessions also helped the School identify relevant material, contacts and links to external and internal learning products, minimizing duplication in developing learning content and helping to promote sharing of resources.

Key questions

This report reflects the findings from the following key questions that were asked of each of the 7 external groups:

- What would make the ILS unsuccessful?

- What do public servants need to know to develop respectful relationships with Indigenous peoples?

- What are the resources? Who are the people who can speak to this?

- How do we address bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism?

- How will this learning series contribute to change?

This report also reflects the findings from the questions asked of federal public service employees:

- What knowledge, skills and abilities do public servants need to work effectively with Indigenous peoples and to develop and implement public policies, programs and services that are relevant to and reflective of Indigenous realities?

- How can the ILS address bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism?

- How do we continue to work with you to identify linkages with your network or community and ensure Indigenous learning content is relevant and aligned?

In order to reflect First Nations, Métis and Inuit diversity and the diversity among the respondent groups, this report highlights unique perspectives within the text and in side-bars, images and information panels.

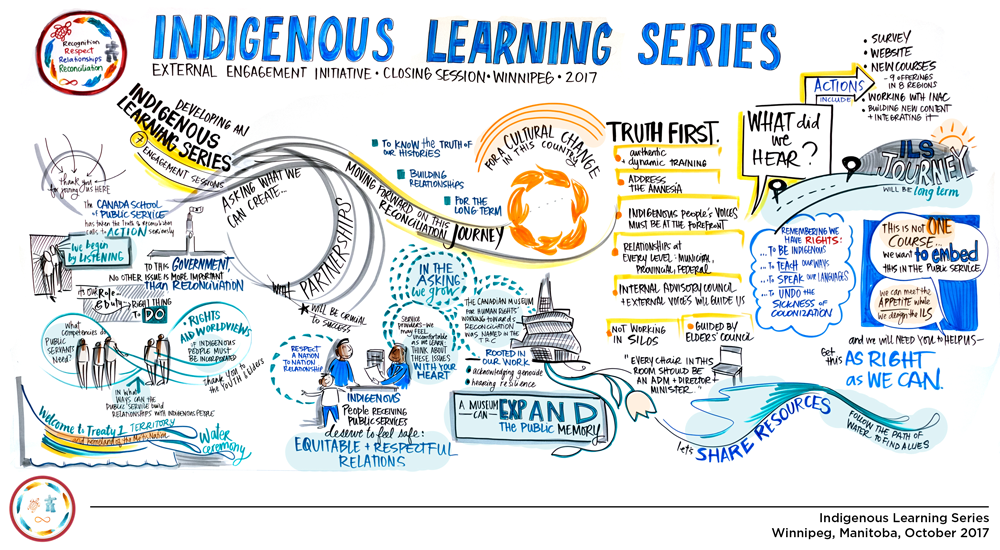

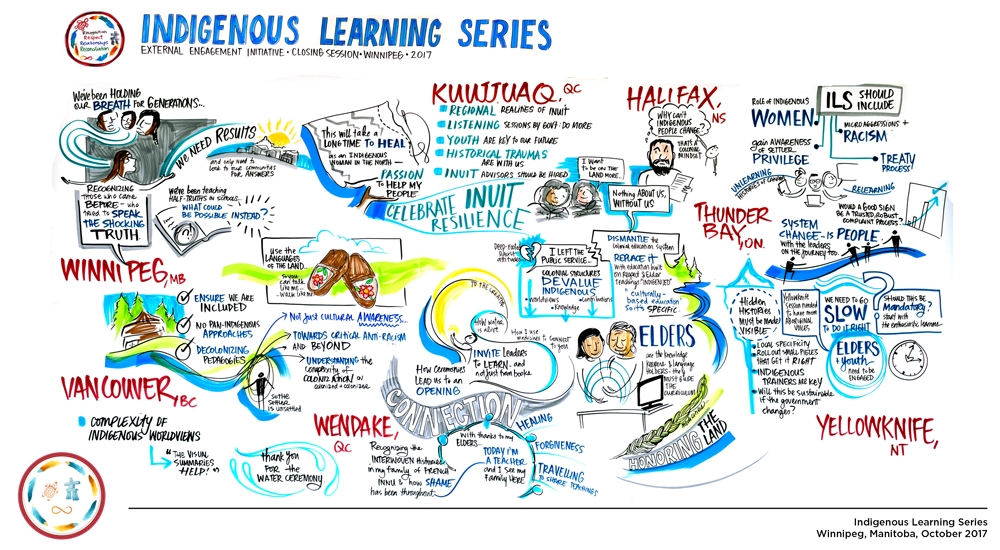

Additionally, artists attended the sessions with external groups to visually capture the discussions. The images used throughout this report are taken from the resulting artwork. The images found in Appendix C represent the conversation that took place during the closing session in Winnipeg, Manitoba, on October 31, 2017.

External Engagement Sessions

Eight sessions were held in 7 regions across Canada from March to October 2017. Locations included Winnipeg, Vancouver, Kuujjuaq, Wendake, Halifax, Thunder Bay and Yellowknife. A total of 159 participants attended, including First Nations, Métis and Inuit, Elders, Indigenous organizations and subject matter experts in the field of First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, history and learning. According to evaluation feedback following the sessions, most participants were hopeful about the possibilities of the ILS.

Internal Engagement Sessions

The School also conducted internal engagement sessions with federal public service employees from various levels and fields from March to November 2017. More than 300 Indigenous and non-Indigenous employees participated in on-site and virtual sessions that included crowdsourcing, presentations and engagement activities.

To ensure that engagement efforts would reach and address the needs of as many employees as possible, sessions were also held with internal communities and networks such as Indigenous employee circles, functional communities, Regional Federal Councils, the Indigenous Executives Network, and learning communities.

The objectives of these internal engagement sessions were:

- to provide information about the ILS

- to seek feedback on what public service employees need to know

- to ensure that products would be relevant and learner-centred

Some of the following questions were asked only of external participants and not of federal public service employees, or vice versa. Findings from internal engagement sessions, however, sometimes shed light on the themes covered in external discussions; the views of federal public service employees are therefore included where relevant and as indicated.

What would make the Indigenous Learning Series unsuccessful?

External engagement session participants (with reflections from federal public service employees)

This question was asked in each of the external engagement sessions to determine what should be avoided in designing the ILS and to ensure that the shortcomings of past initiatives are fully understood and not repeated.

The discussion brought forward the following main errors that the ILS should avoid:

- disregarding First Nations, Métis and Inuit input and involvement

- perpetuating paternalistic views and racism

- using a misguided or inappropriate approach

- being inadequately planned and resourced

- being developed without any measures of accountability

- forgetting its audience

Insights from Halifax: Indigenous Knowledge

Between 2015 and 2017, Maritime Electric undertook a cable interconnection upgrade between the provinces of New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. They used light detection and ranging technology to find the easiest way across the Northumberland Strait. Indigenous peoples, however, already knew that there was an underground body of water that had begun to form 9,000 years ago.

Disregarding Indigenous input and involvement

Each of the groups stated that the ILS must be informed by First Nations, Métis and Inuit input and involvement from development to implementation. The ILS would be unsuccessful without, for example, First Nations, Métis and Inuit trainers and educators or true research efforts before developing course material. Consultation with First Nations, Métis and Inuit is essential and can be done in many ways, such as through an external advisory committee of Elders.

First Nations, Métis and Inuit should have the opportunity to share their success stories and demonstrate models of relationship building and interpersonal respect. Not involving First Nations, Métis and Inuit would demonstrate that the ILS is not committed to real, deep understanding and change.

Using a pan-Indigenous approach or grouping all nations and regions together would also contribute to an unsuccessful ILS. All of the groups stressed the importance of recognizing and learning about the differences between the nations, their languages, cultures and protocols and how history has affected them. This means moving away from a stereotypical or romanticized image of First Nations, Métis and Inuit, which is all too present in popular culture, folklore and media (for example, Pocahontas or Dances with Wolves). It also means avoiding a monolithic, inaccurate and disrespectful portrayal of First Nations, Métis and Inuit as a single, undifferentiated group.

A braid of sweet grass is curved upwards like a feather with the word "medicines" in small font underneath the tip of the braid. In larger font beneath the braid of sweet grass it says "honouring the land."

Language is also highly important. The ILS must avoid inaccurate content and poor translations. It must also incorporate vocabulary and terms from Indigenous languages.

A commitment to a culturally relevant and appropriate ILS would also include a focus on truth, accuracy and complete information. In addition to a pan-Indigenous approach, several other errors should be avoided, such as omitting the intergenerational perspective; not incorporating cultural knowledge and context; and not using Indigenous knowledge in course material.

Indigenous knowledge "forms a part of a larger body of knowledge, which encompasses knowledge about cultural, environmental, economic, political and spiritual inter-relationships."Note3 One example is the knowledge built up over the years by those living in close contact with nature. Many of the groups mentioned that the ILS would be unsuccessful if it did not use this form of experiential knowledge as one of the cornerstones of its course material.

Perpetuating paternalistic views and racism

Continuing to use a paternalistic or racist approach—such as one that does not acknowledge the need for change—would also make the ILS unsuccessful.

A paternalistic approach, founded on prejudice and assumptions, is insincere and disrespectful and attempts to rewrite history (by "whitewashing" or "whitesplaining"). It considers only one perspective to be accurate or correct.

Many of the groups mentioned that the ILS would be unsuccessful if it perpetuated a Eurocentric framework or Western model, both of which are seen to be harmful and destructive and do not take into account First Nations, Métis and Inuit world views and perspectives. During the opening session, the Winnipeg group emphasized that if current ways of thinking are not questioned, the ILS will not be able to speak with any relevance about identity, privilege, social inequity or human rights.

Similarly, a racist attitude disregards the impacts of the effects of colonialism on First Nations, Métis and Inuit, doubts their ability to think for themselves, thinks that First Nations, Métis and Inuit need to be "fixed" or believes that First Nations, Métis and Inuit should simply "get over it." Participants from Wendake said that if unchanged, such attitudes would result in unacceptable living conditions in certain Indigenous communities continuing to be ignored.

Finally, tokenism—making very minimal or symbolic efforts—should also be avoided. All of the groups pointed out that the ILS would be ineffective, if not dishonest, if it were only done symbolically. Participants from Vancouver specified that the ILS would be particularly unsuccessful if it was perceived to be part of a manipulative or hidden agenda, where "reconciliation" is used as a political distraction without any real intent to make changes.

Using a misguided or inappropriate approach

The wrong approach to learning could be a critical mistake. The ILS would be unsuccessful, for instance, if the educational approach were

- boring or humourless

- too administrative or theoretical

- overly bureaucratic or procedural

If courses are "dumbed down," cater to low expectations, are not change-oriented or seek to maintain the status quo, participants may not feel motivated to take the content to heart. Courses may also have little impact if they only focus on differences while omitting the similarities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples or if they only focus on the past while neglecting the present and the future.

A winged heart next to the word "respect."

All of the groups mentioned that the ILS would be unsuccessful if it were too focused on the comfort of the participants. Healthy discomfort—generated, for instance, by asking hard or uncomfortable questions—should be encouraged in a safe space. As an example of an "uncomfortable" approach, many of the groups mentioned their appreciation for the blanket exercise,Note4 which uses role play to demonstrate the injustice of colonialism.

The Yellowknife group cautioned against focusing too much on reconciliation and not enough on truth. The courses should seek to share the "real truth" and acknowledge suffering, while teaching people how to lead "from the heart" to build relationships and move forward together. A course that makes its participants feel guilty would be unsuccessful and unproductive; external participants felt that learners should be inspired to become "allies" as they pursue further learning.

Being inadequately planned and resourced

Session participants considered planning and logistics to be equally important in developing the ILS in a thoughtful, sustainable way. All groups indicated the need for a well-planned and thorough learning series that is accessible in its location and technology, flexible instead of "one size fits all," and properly equipped with funding and human resources.

Most participants see the ILS as a learning journey that should be well supported. It should be well integrated into all programs and backed by strong leadership commitment, trained resources and well-defined objectives. The group from Vancouver specifically noted that the ILS should not be run like many government programs: too short and constrained by tight budgets and limited resources.

Ideally, learning products should also be released over a certain period of time, as opposed to existing as one-time events; they should not be released simply to check a box. Learning in the ILS should include experiential and peer-to-peer components.

Being developed without any measures of accountability

Measurement and accountability were raised as key ways to ensure that the ILS is developed thoughtfully, that it is culturally appropriate and relevant, and that it is driven by a need for real change.

The ILS would be unsuccessful if it lacked accountability, particularly from public service leadership, for

- the accuracy of its content

- its implementation

- its promotion and continuity

Similarly, failing to measure and assess the ILS before and after it is implemented would prevent the ILS from being taken seriously or continuing to improve. The ILS might also be unsustainable if it lacks a well-planned strategy that accounts for collaboration with partners, investment, leadership commitment, measurement and follow-up.

Finally, some of the groups talked about longer-term responsibility for change. External groups noted that while the ILS should not be anchored in an ideology of guilt, neither should it place the onus of change solely on First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Forgetting its audience

The ILS must not forget to consider learners' perspectives. For example, participants from Yellowknife and Winnipeg stated that the ILS could risk alienating learners if it doesn't reflect the needs of its audience or ensure buy-in from all levels. Although uncomfortable discussions should be encouraged, this should occur in a safe space: learners should feel supported and empowered to take their learning further, eventually becoming supporters and agents of change. Furthermore, participants noted that forgetting about those who are supportive of respectful relationships or not using these individuals to their full potential could ultimately detract from the impact of the ILS.

What do public servants need to know?

External engagement session participants and federal public service employees

This question explored what learners should know to develop respectful relationships with First Nations, Métis and Inuit—in short, what knowledge should form the content of the ILS and what skills and competencies should be its learning objectives.

Insights from Wendake: Success

A successful learning approach considers the audience by

- accompanying cultural shocks with resilience training

- ensuring accessibility

- adapting it to the culture

- encouraging relevant and applied learning

Knowledge

Overall, participants noted that learners should be taught about First Nations, Métis and Inuit history, contemporary realities and issues, world views, languages, knowledge and governance. They should also be sensitized to the key concepts and tenets of anti-discrimination and social justice, learning how to address racism and how to build relationships. Furthermore, they should learn the complete truth, including the impact of legislation, legal rights and the meaning and implications of reconciliation.

Participants suggested the following subjects.

History

An outline of a person with their hands on their hips stands next to a pile of 3 books crossed out with a large X. A speech bubble coming from the person says "Re-evaluate history."

A complete timeline covering pre-contact, post-colonization and the current realities of First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Region-specific: contemporary

Region-specific knowledge about First Nations, Métis and Inuit today, with a focus on their diversity, including

- demographics

- business and home life

- figures and heroes

- governance and leadership

- successes (ideas and contributions)

- government programs for First Nations, Métis and Inuit

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit popular culture and arts

- spiritual leadership

Region-specific: world views

Region-specific knowledge of

- historical and contemporary culture

- ceremonies, sacred items, myths and stories

- etiquette and protocol

- languages

- traditional values

Language and key terms

Indigenous languages, terminology and the concepts necessary for developing respectful relationships, including

- respect

- equity

- diversity

- discrimination, bias and racism

- cultural safety

- respectful terms and meanings (for example, "Indigenous" versus "Aboriginal")

- Indigenous languages, diversity, terminology and vocabulary

"The [goal should be] moving from unconscious incompetence to

conscious competence" – Halifax participants

Legal rights, professional practices, legislation and governance

Legislative and legal decisions and professional practices, including frameworks, documents, and factors that affected First Nations, Métis and Inuit historically and that continue to affect them today, such as

- the Indian Act (positive and negative aspects) and treaties

- the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

- human rights legislation

- treaties and land and resource management

- traditional and contemporary justice systems, legislative practices and forms of governance

- human resources obligations and hiring practices

- laws and legal rights, court cases and precedents (for example, R. v. Calder, R. v. Sparrow, R. v. Guerin, Tsilqot'in Nation v. British Columbia, Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, R. v. McIvor)

Insights from Halifax: History

Evolution of Maliseet and Mi'kmaq societies

- Age of Independence

- Age of Contact

- Age of Reciprocity

- Age of Destruction

- Age of Healing and Revival

Truth

The complete and sometimes uncomfortable truth about

- colonization

- contemporary violence against Indigenous peoples (for example, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, "Starlight Tours," Indian Residential School system, the "Sixties Scoop")

- oppositions, disputes and confrontations (for example, Gustafsen Lake Standoff, Oka Crisis, Clayoquot blockade, Haida Gwaii blockade)

- racism from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples

- other examples of discrimination and their resolution, where applicable (for example, Apartheid)

Social justice and addressing racism

Understanding and unpacking bias and racism, as well as ways of overcoming conflict, using concepts such as

- privilege, unconscious bias, colonialism, avoidance and power

- anti-harassment and anti-racism

- strength and resilience

- similarities and differences between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples

- cultural sensitivity

"The steps toward reconciliation are Recognition, Respect and Relationships." – Wendake participants

"It's not about what we know, but how we act. Education should follow the five Rs: Responsible, Relevant, Reciprocal, Respectful, and Reverent." – Vancouver participants

A larger person is seated with one hand up as if expressing something; a smaller person has their arm around the shoulders of the larger person. The image is entitled "Elders;" below the image, additional text states that "they add history and regional context."

Indigenous knowledge

Learning about topics such as

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit ways of learning

- contributions of First Nations, Métis and Inuit

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge keepers

- Elders

Reconciliation

Understanding reconciliation and asking questions like

- What does "reconciliation" mean?

- What are the goals of reconciliation?

- How do the 10 principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples fit in?

- Why is reconciliation relevant?

- What is your Call to Action?

- What are the barriers and protocols?

- What does reconciliation mean to First Nations, Métis and Inuit?

Relationship building

The key concepts necessary for developing empathy and building respectful relationships, including

- principles of conflict resolution and relationship building

- barriers, triggers, trauma and their effects on relationships

A Wampum belt with 2 thick black stripes on it and fringes on either end. Text in a cloud above the belt says "A wampum belt tells a story."

"Inuit are not all the same. We must learn and teach about the differences. If you don't know, just ask.

Be humble." – Kuujjuaq participants

Skills

Learners should be encouraged to develop personal skills like self-awareness and reflective leadership; interpersonal and cross-cultural skills like relationship building, empathy and communication; and skills related to social justice, like anti-racism and engaging in difficult conversations. These skill sets include

Self-awareness and reflective leadership

- flexibility

- acting with integrity

- tolerance

- understanding bias

- humility

- self-awareness

- politeness

- recognizing value in diversity and other ways of doing things

- honouring differences

- self-motivation

Interpersonal and cross-cultural skills

- negotiation

- conflict resolution

- dialogue

- being authentic

- being empowered and empowering others

Relationship building

- trust

- patience

- collaboration

- sincerity

- tact

- consultation

Communication

- engaging stakeholders

- reading body language

- communicating respectfully

- listening

- speaking plainly

- seeking advice

Empathy

- deep understanding

- being accountable

- social-emotional intelligence

- openness

- understanding other perspectives ("walking in our moccasins")

Anti-racism

- recognizing, calling out and responding to racism

- understanding and analyzing unconscious bias (for example, using approaches similar to gender-based analysis)

Engaging in difficult conversations

- embracing discomfort

- sensitivity

- willingness to learn

- critical thinking

- asking questions

Observations from Thunder Bay and Vancouver: the Seven Sacred Laws (Grandfather Teachings)

Participants noted that the Seven Sacred Laws or Grandfather Teachings can provide insight about the potential types of skills that could be developed for respectful relationships.

- Truth – Debwewin: To Speak Only to the Extent We Have Lived or Experienced

- Humility – Dabasendiziwin: To Think Lower of Oneself (in Relation to All That Sustains Us)

- Respect – Manaaji'idiwin: To Go Easy on One Another, meaning all of Creation

- Love – Zaagi'idiwin: Unconditional Love Between One Another, meaning all of Creation—including humans and non-humans, seen and unseen, of yesterday, today and tomorrow

- Honesty – Gwayakwaadiziwin: To Live Correctly and with Virtue

- Bravery or Courage – Zoongide'ewin: To Live with a Solid, Strong Heart

- Wisdom – Nibwaakaawin: To Live with Vision

Definitions from the Seven Generations Education Institute: Seven Generations Education Institute

Competencies

Personal competencies

- applying anti-oppressive behaviours and principles (that is, anti-racism and anti-harassment)

- identifying and evaluating behaviours

- building compromise

- being self-aware

Insights from Yellowknife: Competencies

To be effective, competencies should be structured and well defined. Each competence could be measured using levels. For example:

Level 1: Cultural awareness

Level 2: Cultural sensitivity

Level 3: Cultural humility

Level 4: Cultural safety

Interpersonal competencies

- building sustainable relationships with the goals of community and collaboration

- promoting equality

- being welcoming, compassionate, open-minded and trustworthy

- engaging and consulting others

- demonstrating effective leadership

- leading with the heart

- developing intercultural knowledge and abilities

Change-related competencies

- Embracing deep change vs. engaging in tokenism

- Embracing attitude change (self-awareness and reflection)

- Applying learning in the service of change

A large coniferous tree with the root system exposed stands next to the words "Teaching can be many things: ceremony, art, dance."

Participants from Yellowknife also suggested that it would be beneficial to go "beyond" the ILS by

- building cultural competencies into everyday work and performance assessments

- making learning and sensitization part of the larger structures

- advocating for change

Public service employees from the Canada Revenue Agency stated that public servants need to understand the history of First Nations, Métis and Inuit, particularly what led to the need for reconciliation.

Other considerations

In addition to covering the knowledge, skills and competencies discussed above, participants in Wendake suggested that learning from the ILS should be applicable and relevant to work in the public sector, providing an answer to the question, "what's in it for me?"

What are the resources that can help inform, develop, and implement the ILS?

External engagement session participants (with reflections from federal public service employees)

Insights from Thunder Bay:

Women's Voices

Include women's voices: they are the carriers of culture and life givers. They can also effect change.

Overall, it was acknowledged that the ILS should be supplemented by close consultation and engagement with various stakeholders and should build on existing research and materials. These resources can help inform the learning process by sharing expertise and insight. Many of the resources identified could be used to ensure that content is accurate, useful and culturally relevant.

Resources and references recommended during the engagement sessions are summarized below and outlined in greater detail in Appendix A.

Two smiling faces, one older and one younger wearing a baseball cap. Speech bubbles show the older one saying "Indigenous" while the younger one says "voices."

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit resources include a broad and diverse range of voices from different generations, including Elders and youth, and Canadian regions, as well as from reserves and remote, rural, urban and Northern communities.

- Expert resources include educators knowledgeable in First Nations, Métis and Inuit histories, cultures, and contemporary issues as well as in anti-racism frameworks and diverse world views. Government employees in a variety of fields (for example, human resources) should also be included.

- Academia includes staff, alumni, graduate students and post-secondary institutions that have centres of expertise related to Indigenous studies.

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit networks and organizations serve, represent or advocate on behalf of First Nations, Métis and Inuit across Canada and offer research, information, training, advocacy and opportunities for involvement and solidarity.

- Reference material includes reports, legal and legislative documentation, film, books, articles, research papers, teaching tools and conferences.

- Other perspectives whose involvement demonstrates a commitment to respecting diversity and a broad range of perspectives include women, other minorities, people with disabilities, youth and children of all races, the audience of the ILS and those who have undergone a change of perspective.

How do we continue to work with public servants to identify linkages with networks and communities and ensure Indigenous learning content is relevant and aligned?

Federal public service employees

As ways to identify and build on linkages with networks and communities, internal participants spoke about building a community of practice made up of subject matter resources, leaders and learners.

Three circles, small, medium and large, are arranged in a diagonal row with each overlapping the next. The smallest one at the bottom is labelled "me," the middle circle "us" and the third and top circle "Canada." The image is entitled "transform the public service."

For example, representatives from the Canada Border Services Agency noted that at higher levels, one way to model the community of practice may be a committee made up of First Nations, Métis and Inuit leaders and Elders, executives responsible for policy or programs and a mix of First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners or stakeholders, all equally represented. Others spoke about involving, engaging and connecting departmental learning and development sectors or Indigenous consultation units with Elders, youth networks and other First Nations, Métis and Inuit networks. More broadly, a community of practice would involve voices from every corner of the public service and pay close attention to every individual voice.

Many of the internal groups consulted discussed the mechanisms and roles needed to promote linkages. These include, for example, departmental champions, awareness events held by WebEx or in person and annual roundtable events with management and others.

Internal participants mentioned the importance of continuous learning, in-person sessions and discussions and follow-up surveys and in-person consultations. Employees from Service Canada suggested learning and discussion about the cultural backgrounds, lives and interests of employees, including discussions with First Nations, Métis and Inuit about their customs, spirituality, traditions, practices and interactions with the Canadian judicial system. These approaches promote dialogue and experiential learning, allowing participants to contribute to the broader discussion and to feel personally involved.

To ensure that Indigenous learning content is relevant and aligned, internal participants noted that some courses—such as those about reconciliation—should be applicable to all of government, but that courses specific to departments or portfolios are equally important. Specialized learning for different career groups (for example, functional specialists, frontline workers, policy, and leadership) was also highlighted as important. Finally, participants raised the need for personal resilience skills and training to support the uncomfortable or emotional conversations and situations that may arise from some of the learning content. Some internal participants also discussed the need for further consultation, suggesting discussions with public service employees and with First Nations, Métis and Inuit to determine what each side sees as barriers and ways in which these issues could be best approached by the ILS.

How do we address bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism?

External engagement session participants and federal public service employees

Addressing bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism is a lengthy process that requires commitment, willingness and sensitivity. Input from both external engagement participants and federal public service employees is summarized below under the following themes:

- understanding the realities

- disrupting current ways of thinking

- involving, empowering and equipping the right people, especially First Nations, Métis and Inuit and public service leaders

- moving towards deeper awareness and change

- committing to the full, complex journey

The participants believed the ILS can contribute to each of these themes if it is thoughtfully and respectfully planned and executed and if it is fully supported and integrated.

Understanding the realities

As mentioned by all of the participant groups, one way to address bias, stereotypes, and anti-Indigenous racism is to develop an understanding of historical and current issues and relationships. This means understanding the nuances of and differences between stereotypes, bias, discrimination and racism.

Insights from Thunder Bay: The Leaves of Injustice

It is important to understand the leaves of injustice, but we must also hack away at the root. There is a natural growth of the tree, but there are also sicknesses. We must expose people to the branches of the sick tree and help people to understand those branches.

Skills are required to work with others. We must help people to see the tree of truth and justice that lives on the land. There is also an Indigenous root to the tree, a natural law.

According to participants, current issues also reflect deeper imbalances of power and colonial mindsets like assimilation, which persist today in paternalistic behaviours, abuses of power and tense race and power relations. It is important to understand the way in which racism and power imbalances have led to social inequities generally and to traumatic events more specifically. These events have had and continue to have an impact on First Nations, Métis and Inuit today—for example, through intergenerational trauma. To begin to understand the way forward, learners should first learn about "how we got here."

Participants also noted that racism has not only been present in Canada as a whole, but also within the public service. Participants stated that learners should learn about historical and contemporary racism, as well as how it is still institutionally and societally embedded in current government policies. At an individual level, privilege and culturally insensitive practices like cultural appropriation also need to be understood, as do roles and identity.

A sign in the shape of an arrow on two posts in the grass reads "Success."

All of the groups proposed that culturally relevant content about Indigenous peoples should reflect First Nations, Métis and Inuit diversity—every nation is unique and has experienced bias, stereotyping and anti-Indigenous racism differently. For example, participants from Kuujjuaq mentioned that it is important not only to understand violence generally, but also to be able to apply a regional lens. This helps learners understand regional specificities, such as the "bullying" in the North from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous leaders.

Success stories and local values like humility and love help balance this content and illustrate the value of First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, knowledge and resilience. However, it should be noted that the definition of "success" is culturally relative. For example, participants from Winnipeg mentioned that where success might mean high-paying careers to the Canadian majority population, for First Nations, Métis and Inuit, success may mean being better rooted in the community.

Participants mentioned that course content should ideally include a blend of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous forms of knowledge. This makes the ILS accessible to all learners and ensures that the content is culturally relevant. A mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous teachers could also help diversify perspectives. Finally, knowledge and education about racism, privilege and bias should also be supported by course content related to human rights and ethics.

Disrupting current ways of thinking

This is seen as a process that begins with debunking myths and dismantling preconceived notions—in short, teaching people how to stop "othering." To illustrate this, the Vancouver group clarified that learners need to understand that "[Indigenous] rights do not end where [non-Indigenous] rights begin." Rather than employing an "us" versus "them" mentality, all peoples' rights should be respected equally and at all times.

As mentioned by many participants, changing perspectives sometimes involves making people uncomfortable, perhaps by shedding light on everyday practices that are perceived as innocent but that may have a negative impact in practice. The Vancouver group mentioned that untangling concepts like "multiculturalism" and "diversity" is a step in this direction. The Halifax group pointed to identifying "soft racism" and unconscious bias as necessary steps, while participants from Thunder Bay and Yellowknife suggested introducing a bias test, similar to the one used in gender-based analysis as a way to expose potential hidden bias.

Identifying stereotypes and idealized images of First Nations, Métis and Inuit and calling out tokenism and micro-aggressions (which include, for example, asking questions such as "Where are you from?" or "Where were you born?") in the workplace contribute to disrupting current mentalities. Challenging decisions and enforcement and demanding accountability—from public service leaders, for example—is another step.

Participants stated that mindsets can also be changed when learners acknowledge and understand the Eurocentric framework and colonialist lens that have traditionally been used to define Canadian-Indigenous relations, as well as how this has contributed to the rewriting of history and to "historical amnesia." Challenging previous ways of thinking could also enable learners to identify and understand the interconnectedness of systemic and individual racism while exposing paternalistic perspectives and mentalities like the "get over it" attitude. Disrupting set ways of thinking can also allow learners to understand the truth behind myths and misconceptions.

Finally, both internal and external groups asserted that when learners recognize other perspectives and contextual issues, they can begin to understand the link between systemic racism and negative social indicators and intergenerational trauma. These symptoms, participants held, were part of recovery from cultural genocide.

Participants also acknowledged that this process of disrupting current mindsets requires time, commitment and empathy; it will be neither easy nor comfortable. Indeed, participants from Kuujjuaq cautioned that it will be important to be prepared for some racism and resistance.

Involving, empowering and equipping the right people

Participants saw this task as related to the shared responsibility for everyone to work together towards a common purpose. It also involves introducing non-Indigenous responsibility, empowering and equipping those who are sensitive to historical and contemporary issues and are personally committed to bringing about change.

Involving public service leaders—from managers to senior executives—could also help to give the ILS the weight and significance it needs to go beyond an exercise in tokenism. Ensuring and leveraging buy-in from First Nations, Métis and Inuit partners is equally important to ensure that the ILS is reflective, respectful and culturally relevant.

In the views of participants, empowering and equipping the right people also means that the ILS should consider introducing measures of accountability, defining clear requirements for learners and making its courses adaptable and accessible.

Moving towards awareness and change

Insights from Thunder Bay: Understanding

What needs to be understood?

- The OTHER: cultural awareness and sensitivity

- The WHAT: cultural competence

- The HOW: cultural humility and safety

- The GOAL: equitable services

Participants see commitment, openness and understanding as the facilitators of awareness and change. Specifically, these are achieved by creating a culturally safe and respectful environment instead of one laden with guilt and blame and encouraging healthy differences of opinion and discussion. For example, Atlantic employees from the Canada Borders Services Agency noted the importance of an environment where questions can be asked and answered respectfully without either side being seen as racist. Supported by this framework, learners are better able to develop self-awareness, as well as the compassion, empathy, love and kindness required for connection on a deeper, more personal level. This approach enables learners to discuss a range of perspectives, address strong feelings, such as anger, and build trusting relationships. In order to accomplish this, participants felt that the ILS should develop a safe space and encourage openness to all ideas, two-way listening and truthful discussion of broader issues and ideas.

Truthful discussions should address systemic racism—as manifested, for example, in status identity and the reserve system—and should be honest about harmful policies, as well as exploring methods to reduce racism, harassment and bullying in the public service.

Internal participants on GCconnex suggested that the ILS should form part of a broader societal discussion, even going beyond the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's Call to Action #57. It was suggested that the ILS should go to the very heart of policy making, unravelling systemic racism and bias and embracing First Nations, Métis and Inuit and their cultures.

Certain institutional steps were also recommended to support the ILS's contribution to awareness and change. These include, for example, clearly identifying desired impacts for all learners, making sure the ILS is well resourced, measuring and acknowledging success and building transparency into the process. Institutional steps might also consist of the ILS contributing to anti-harassment policies and anti-racism training.

Committing to the full, complex journey

Insights from Yellowknife: Bias

The path to addressing bias: learning, unlearning, and relearning

Participants agreed that the ILS should not be seen as a one-time, checkbox activity and that it should be culturally relevant and thoughtfully executed. A scaffolded, "building block" learning approach was proposed as a way to slowly introduce concepts and help learners progressively develop empathy, knowledge and respectful relationships over a longer period of time. The external groups and the internal participants alike emphasized that the ILS should be seen as a safe space, include experiential learning in its foundation and be part of a holistic, lifelong learning journey. As participants from Kuujjuaq pointed out, reconciliation is a long process that requires a great deal of self-awareness.

"Public servants should spend time with Indigenous groups [they] are working with on the terms of the Indigenous groups' choosing. There should be less focus on outcomes-based interactions and more focus on relationship building." – Internal participants, Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency.

How will this learning series contribute to change?

External engagement session participants (with reflections from federal public service employees)

External participants offered a variety of constructive responses related to short-term, medium-term, and long-term change, often speaking more generally about how real change in Crown-Indigenous relationships might look. The ILS is seen as a potentially important first step that would represent a concrete effort from the Canadian government towards meaningful change.

A multi-tool pocket knife with a mini blade, a pencil, scissors, a mini saw and a heart-shaped pick is surrounded by words. The words are: self-awareness, safer spaces (ok with being uncomfortable), education (know social, colonial histories, challenge western biases! build foundational training, then add levels) and know histories (and the present too).

Short-term change

In the short term, change could consist of debunking stereotypes and increasing sensitivity, both in the federal public service and among Canadians broadly. This would result from acknowledging the need for change; understanding individual and collective privilege, power relations and racism; and committing to changing thoughts and behaviours. Short-term change would occur when non-Indigenous people not only begin to recognize the merit of First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, values and knowledge, but also begin to incorporate these realities into the workplace and their day-to-day lives.

Debunking stereotypes and reducing racism

In the short term, the groups consulted for the ILS would like to see the status quo interrupted. This means shifting mindsets and behaviours, dispelling myths and confronting stereotypes. The Vancouver group specified that one cognitive shift would include no longer thinking of Indigenous peoples as "wards of the state." Similarly, the Winnipeg group mentioned that new mindsets might also include sensitivity towards First Nations, Métis and Inuit perspectives and views—for example, acknowledging that "Canada 150" was not a celebration for all.

Participants agreed that this shift in behaviour would be best accomplished in a safe space where educators and learners can address emotions, resistance and guilt together while understanding First Nations, Métis and Inuit truths and local histories and cultures.

Insights from Internal Participants (Fisheries and Oceans Canada): Hiring Practices

There is a need to hire people into the public service who have a deeper cultural awareness. The softer skills in an interview process in relation to cultural awareness and understanding need to be addressed; superficial quick answer questions will not reveal racist tendencies.

In the public service

Participants expressed the view that change in the public service might occur when employees become more sensitized to racism and the preconceptions and misconceptions that take place day to day in the operations of government and in the ordinary interactions of employees. Beyond the individual level, re-evaluating federal structures could facilitate government-wide change. With the right level of support and buy-in from public service managers and leaders, this could include developing sensitivity and awareness among public service employees, introducing First Nations, Métis and Inuit values in the workplace and creating a new knowledge base that includes First Nations, Métis and Inuit. Participants from Kuujjuaq, for example, noted that this would contribute to a better workplace environment overall.

Participants identified awareness of stereotypes and racism, accessibility and a sense of welcome for First Nations, Métis and Inuit as the attributes of a safer and more inclusive public service. These qualities would also open the doors to greater representation of First Nations, Métis and Inuit employees and a more diverse workforce in general. This step requires revisiting hiring practices and processes as well as a willingness to hire more First Nations, Métis and Inuit employees. The Winnipeg group also specified that unions must also develop sensitivity and acknowledge First Nations, Métis and Inuit rights and needs in the workforce.

Recognizing and leveraging value

Insights from Halifax: Generational Knowledge

Generational knowledge is like sweetgrass. The first generation plants it, admires its beauty and leaves it for seven generations. After seven generations, it is picked and used as medicine.

Participants from Vancouver, Winnipeg, Kuujjuaq, Halifax and Thunder Bay pointed out the need to recognize and leverage the value of First Nations, Métis and Inuit to move forward. This includes, for example, recognizing, understanding and integrating First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge, including generational knowledge, and holistic education styles in the public service and more broadly. A strengths-based approach also highlights First Nations, Métis and Inuit successes and local perspectives and world views.

Participants felt that change could result from moving beyond simply learning about Indigenous perspectives to involving First Nations, Métis and Inuit and using their knowledge in leadership. Public sector leaders could also play a bigger role in modelling change.

Medium-term change

Medium-term change might occur when learners move past understanding and begin to develop empathy and compassion, demonstrating a willingness to build relationships and work together. Medium-term change in the public service specifically might include the introduction of measurement and accountability for the ILS and for other initiatives intended to promote equality and equity among Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

Developing empathy and building relationships

Change also occurs when people are equipped with the right level of knowledge and empathy to begin to develop relationships. This process is seen to have two main benefits:

- providing space to discuss trauma and challenges

- enabling people to work together

A pair of moccasins, each of them beaded with a single flower and leaves, with rolling hills and a large cloud in the sky. The words "use the languages of the land" appear beside the moccasins.

For many First Nations, Métis and Inuit, relationship building is not only a core value and skill, but also a step in the process of recovery. For example, participants from Wendake specified that building relationships is a way to develop respect, teach patience and give a voice to those who have been silenced in the past. It also allows individuals and groups to emphasize humanity, develop empathy and compassion and understand the "people factor" in relationships, including past experiences, triggers and trauma.

In line with the suggested experiential learning approach, people develop empathy when they understand truths and realities and witness their impact first-hand. Participants from Yellowknife suggested an approach that encourages an open flow of ideas, stimulates discussion about difficult issues and calls out disrespectful or inappropriate behaviours. Similarly, participants from Thunder Bay suggested that a relationship-building and empathy approach could validate and support emotions while acknowledging lived realities.

A widely held view was that an inclusive, empathy-driven approach also ensures that learners are accompanied by ongoing support, collaboration and trust. Learners, managers and leaders are thus encouraged to become "change agents" and should be supported in their journey towards confidence and engagement. Ultimately, this approach seeks to empower and mobilize learners to be self-aware, respectful and collaborative, working closely with First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Introducing measurement and accountability

In the medium term, change could also include greater sensitivity to First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, histories and realities among the senior ranks of the public service. The ILS should also seek to create ways to measure outcomes and enforce accountability. For instance, participants suggested defining learning outcomes as objectives for each skill set and conducting evaluations (for example, auto-evaluation and collective survey evaluations) for the ILS.

Internal participants proposed ways in which performance might be measured in the broader public service. These included, for example, integrating First Nations, Métis and Inuit measures of success in day-to-day work, including measurable cultural competencies in job descriptions, conducting a Workforce Analysis Survey or adding questions to the Public Service Employment Survey about the safety and retention of First Nations, Métis and Inuit employees.

With respect to accountability, participants from Wendake suggested creating a watchdog position to make sure outcomes are met. They also clarified that each level of government—including elected representatives—should be responsible and engaged.

A long, curved path leads to the sun at the horizon in the distance. On either side of the path are signs that show single words with bullets underneath:

Relationships:

- We must start by being able to AGREE on an equal footing

Respect:

Reconciliation:

- It's far!!

- We need to improve communications

- Educational context

Recognition:

- Participate in cultural activities

The sun is labelled with the word "Themes." Two people, one in a dress, are outlined at the beginning of the path, both pointing towards the sun down the path.

Long-term change

Long-term change could manifest itself at the personal, societal and systemic levels. Participants from Winnipeg referred to this as "micro-macro-level changes and understanding at the systemic and individual levels." Long-term change sets the conditions for developing and maintaining respectful relationships.

Personal change

A speech bubble holds the words "Roll up your sleeves—we have a country to heal." Additional text attributes the words to Elder Gerry Oleman.

According to participants, the ILS can contribute to change on a personal level for both learners and First Nations, Métis and Inuit. Learners would have the opportunity to explore their personal interests and to speak directly to First Nations, Métis and Inuit, asking questions in a safe and open space. They might also learn to take ownership of their own privilege and unconscious biases, ultimately contributing to less racism.

With respect to impact on First Nations, Métis and Inuit, participants from Kuujjuaq highlighted that this initiative and others flowing from the Calls to Action demonstrate willingness to support First Nations, Métis and Inuit in recovering from trauma and improving their mental health. It also validates First Nations, Métis and Inuit trauma and emotions.

Societal change

Societally, the ILS and other initiatives like it can contribute to a sense of equality, where Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous populations work and live together. This means equal status and equal opportunities and security in areas such as education, health, language and employment.

From a broader perspective, participants from Kuujjuaq and Winnipeg indicated that developing awareness and sensitivity and reducing bias, stereotypes and anti-Indigenous racism can help make social inequities—in access to water, housing, education, healthcare, employment, justice, child welfare and other dimensions—a priority issue for Canada. It also helps Canadians acknowledge the impact of trauma and understand the reasons for the gaps in the socio-economic determinants of health among First Nations, Métis and Inuit. Participants from Halifax, for example, noted that possible indicators to measure change might include fewer water advisories, fewer suicides among First Nations, Métis and Inuit youth and increased usage of Mi'kmaq language on signage.

Systemic change

All of the groups spoke about systemic change. While this level falls outside the scope of the ILS, it could play a role by building sensitivity and developing relationships. Deep dialogue and integration of cultural practices could serve as the foundation for systemic change, which could include re-evaluating existing systems and structures and eventually working on, changing or removing policies, legislation, practices, and funding that perpetuate anti-Indigenous racism (for example, the Indian Act). Long-term systemic change necessarily includes engagement from the political sphere and a commitment to societal transformation.

A paper scroll is covered with writing from a feather pen. A word bubble reads "What are the practices and policies that need to change?"

Paving the way for respectful relationships

Long-term change and steps towards reconciliation include an ethical dimension and a moral duty. In line with participants' comments about tokenism, long-term change demonstrates commitment. It is greater than an apology: it recognizes and uncovers untruths and misunderstandings, "clarifies what Canada is about" by recovering history where it has been whitewashed and ensures that past mistakes do not recur, preventing trauma in new generations. Participants from Vancouver called this transition "switching from cultural competence to cultural safety." The ILS can contribute to this change by emphasizing truth along with First Nations, Métis and Inuit world views and knowledge. The ILS can also create a space for dialogue and respectful relationships.

Participants from the opening session in Winnipeg mentioned that this deeper change is facilitated by a safe space where learners and teachers can ask questions and share stories. Such a space focuses on wellness and healing rather than a crisis mindset. This allows learners to change their attitudes, moving forward with fewer prejudices and micro-aggressions as well as improved competencies. They are empowered to think outside the box and become able to withstand discomfort. Participants from Halifax noted that this process is a similar to the work underway to eradicate sexism in the workplace.

Participants from Thunder Bay emphasized that encouraging dialogue leads to better understanding and to caring on a deeper level. Besides reducing racism overall and de-normalizing resistance to change, long-term change also includes support for and cooperation and harmony with those who are committed to change. Participants consider this kind of thinking necessary for reconciliation. Furthermore, reconciliation extends beyond its psycho-social aspects: participants from Winnipeg noted that long-term change also includes the true reversion of land and water to First Nations, Métis and Inuit in a paradigm of "Nation to Nation control."

Finally, participants reiterated that this change will not be an immediate outcome but a long-term, multi-dimensional process.

"Transformation takes time." – Thunder Bay participant

A metal beam balance scale with the words "balance of micro and macro" on it.

Conclusion: how do we do it?

Although "how do we do it?" was not among the questions asked, the external and internal engagement sessions all raised key steps in ensuring the success of the ILS. These included

- involving the right people

- designing the right learning activities

- using appropriate and culturally relevant content

- using the right learning approach

- building in accountability and support

- integrating the ILS into the public service

Involving the right people

Insights from Kuujjuaq: Inuit Voices

Inuit have long been silenced. They have been resilient. They are finally finding their voice.

The ILS would benefit from a variety of perspectives and sources of expertise. For instance, this means involving men and women equally in the development and implementation of courses. Participants from Halifax and Winnipeg also suggested involving a council of Elders or having Elders in residence. The Halifax group elaborated that the presence of Elders contributes to a safe, happy and peaceful environment.

Seven raised hands of rainbow colours and different lengths.

Furthermore, the ILS should be informed by full First Nations, Métis and Inuit involvement, including from women and youth. Collaboration with First Nations, Métis and Inuit should be rooted in a relationship of trust: that is, an assumption that First Nations, Métis and Inuit are competent and will deliver results. Participants from Kuujjuaq specified that when designing and delivering the ILS, Inuit should also be included in planning, development, implementation and monitoring, along with First Nations and Métis.

Expertise can also be drawn from collaboration, partnerships and engagement with all levels of government, from federal to municipal. Finally, participants also suggested including advisors in anti-Indigenous racism and seeking out skilled facilitators.

Designing the right learning activities

Insights from Internal Public Service Employees: Experiential Learning

Experiential learning is holistic and sensitive to beliefs and psycho-social elements. It incorporates support, Indigenous learning styles and humour to reach learners on a personal level.

- on-the-land visits and experiences

- face-to-face teaching and interactions

- role play, case examples and simulated scenarios

- appropriate use of technology

- testimonials, guest speakers and discussions

- peer-to-peer learning

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit teaching techniques

- leading from the heart

- participating in cultural practices

- sharing food and experiences

In each of the sessions, some of the participants emphasized that the ILS should be mandatory for all public service employees, while others felt that learners should participate in the training sessions of their own volition. Participants from Kuujjuaq said it should be available to all Canadians.

Finally, in the internal engagement sessions, the Atlantic Federal Council also mentioned that the ILS course material and content should be well tested and that the ILS should be scalable and well supported by the appropriate resources.

Using appropriate and culturally relevant content

In order to move away from a pan-Indigenous approach, learning should be region-specific and include local histories, traditions and cultures. Courses should also include region-specific Indigenous languages and terminology.

Furthermore, to be appropriate and relevant, ILS course material should explain and reflect the diversity among First Nations, Métis and Inuit and convey the full truth about identity, mental health, historical trauma and violence (including current violence), among other subjects.

Insights from Winnipeg: The Truth about Violence

We must teach about current violence – for instance, it is important to know about "Starlight Tours" and the bodies found in Thunder Bay.

A culturally relevant ILS should therefore include education about

- full, true history

- the impact of policy, legislation and legal decisions

- historical and current stereotypes

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit knowledge

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit cultures, traditions and values

Using the right learning approach

A supportive and thoughtful approach to the ILS would be holistic and sensitive to beliefs and psycho-social elements, accompanying participants in a journey of understanding, self-awareness and change. This means leading from the heart, integrating support structures and resources and using First Nations, Métis and Inuit learning styles. Starting from First Nations, Métis and Inuit world views would help shed light on topics like

- healing and wellness

- internalized colonialism and oppression

- objectification

- cultural competence

An appropriate approach would also include a key relationship-building element, focusing on developing empathy and moving away from "othering" First Nations, Métis and Inuit. Internal participants from the National Managers' Community and the Northern Federal Council mentioned that relationship building is strengthened when it is repetitive, connects people and emphasizes values and strengths. Similarly, Yellowknife participants shared the benefits of an ally approach, which should ideally be safe, supportive, honest and respectful to allow true dialogue and uncomfortable conversations. An ally approach focuses on deepening relationships with those who care. It also starts from a position of self-inquiry rather than one of certainty and includes a variety of perspectives, intergenerational perspectives among them.

Finally, an appropriate learning approach takes its audience into consideration. It is flexible, adaptable, open-minded and inclusive. It encourages a positive learning environment and tone, integrating role models, success stories and humour. It is also applicable and specific.

Building in accountability and support